The Continuing Secular Transition

David Voas

Introduction

The theory of secularization rests on a simple idea: social change tends to follow particular routes. Certain major transformations– such as the industrial revolution, the decline in mortality, or equalization in the status of women– occur exactly once in each society. These transitions are a species of social change, but a rather peculiar one: they are very difficult to undo. Back-tracking is exceptional and temporary.

A transition, then, is a permanent large-scale change. It is not cyclical or recurring; once out, the toothpaste will not go back into the tube. Social dynamics, transnational markets and global communications being what they are, most transitions are likely to occur everywhere eventually. Any claim to historical inevitability would be dubious, but a case can be made for this kind of universality. Where common causes operate in more or less every society, outcomes may be inescapable.

We can use knowledge gained about one transition to illuminate the course and causes of another, even one that seems very different at first sight. Specifically, there are various parallels between the fertility transition– the global decline in birth rates– and what might be called the secular transition, the move away from institutional religion. At first glance the only link that is apparent between the shift from large families to small ones and from general to minority religious participation is that we have had great difficulty in understanding both transformations. By treating them as instances of a specific type of social change, however, it may be possible to apply what we know about one to explanations of the other.

Secularization versus the market model

Just as the theory of demographic transition predicts that modernization will bring about declines first in mortality and then in fertility, the core principle of secularization theory is that modernization causes problems for religion (Bruce 2002). These theories are more aptly regarded as research programs than as single hypotheses; scholars work to identify the mechanisms that produce the predicted outcomes and to assess their relative importance in different circumstances.

At least in the United States, the market model of religion developed in the works of Rodney Stark, Roger Finke, Laurence Iannaccone and others is currently the main rival to secularization theory (Stark & Finke 2000). Their approach is appropriately known as the “supply-side” theory: it focuses on supply, while secularization is largely about demand. The table below shows the key contrasts; subsequent sections will examine each pair of ideas in turn.

Secularization

The social and personal importance of religion varies over time and space. Religion may be important to some people and societies and unimportant to others.

What happens at the societal level also happens at the personal level: modernization undermines religion.

Secular activities and ideas compete with religious activities and ideas. People stop using religion because its perceived benefits are too low and the opportunity costs of involvement are too high.

Reductions in demand are usually permanent. Modern, secular societies will not be converted back to active religiosity.

Supply-side

People everywhere will always want what only religion can promise to provide, and therefore (?!) they will always want religion.

Modernization reduces the institutional importance of religion but not the individual demand for religious services.

If religious consumption is low, it is because of flaws in the market (over-regulation or insufficient competition) or in the quality of God’s sales force (which may be lazy or mediocre).

Religious downturns are merely part of a cycle of decline and revival, governed largely by supply.

For Stark et al., the invariance of demand for religion is the foundational axiom: the second, third and fourth supply-side hypotheses listed above are corollaries of the first. One or another of these conjectures might be true even if their antecedent is false, however, and hence it is worth considering them separately. It is also worth mentioning that there are other alternatives to secularization theory; one may disagree with what follows without necessarily agreeing with the main advocates of the market model (see, for example, Casanova 1994, Davie 2000, 2002, Gill 1999).

The debate over secularization is often hampered by confusion over whether it is the social or the personal significance of religion that is at issue. The influence of religious institutions on other sectors of society is clearly much lower now in the Western world than in the past; no one disputes that the role of religion in the making and enforcing of laws or in the regulation of family life, education, leisure, scientific research, the economy and so on has diminished steadily over a period of several centuries. These changes are intrinsic to the process we call modernization, and there is no serious prospect of them being reversed. Religion might continue to have a public role if it involves enough people with shared views, but even here the tendency in liberal democracies is to view faith as a private matter.

By contrast, there is a great deal of disagreement over the degree to which religious ideas and organizations will continue to influence the attitudes and behavior of individuals in modern society. No one seriously imagines that religion will disappear in the foreseeable future (just as no one supposes that people will stop having children), but the downward trend in most post-industrial societies is striking. What follows is a defense of the idea that secularization is a micro- as well as a macro-level process, i.e., that the late stages of modernization bring declines in religious practice, affiliation and belief.

The evidence

If secularization is a consequence of modernization, then it should be most advanced in the most modern countries. Which countries those are may be contentious, but it is fair to start by looking at the top 20 on the UN Human Development Index (from 2005). In addition to 14 European countries plus Iceland, the list includes the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan.

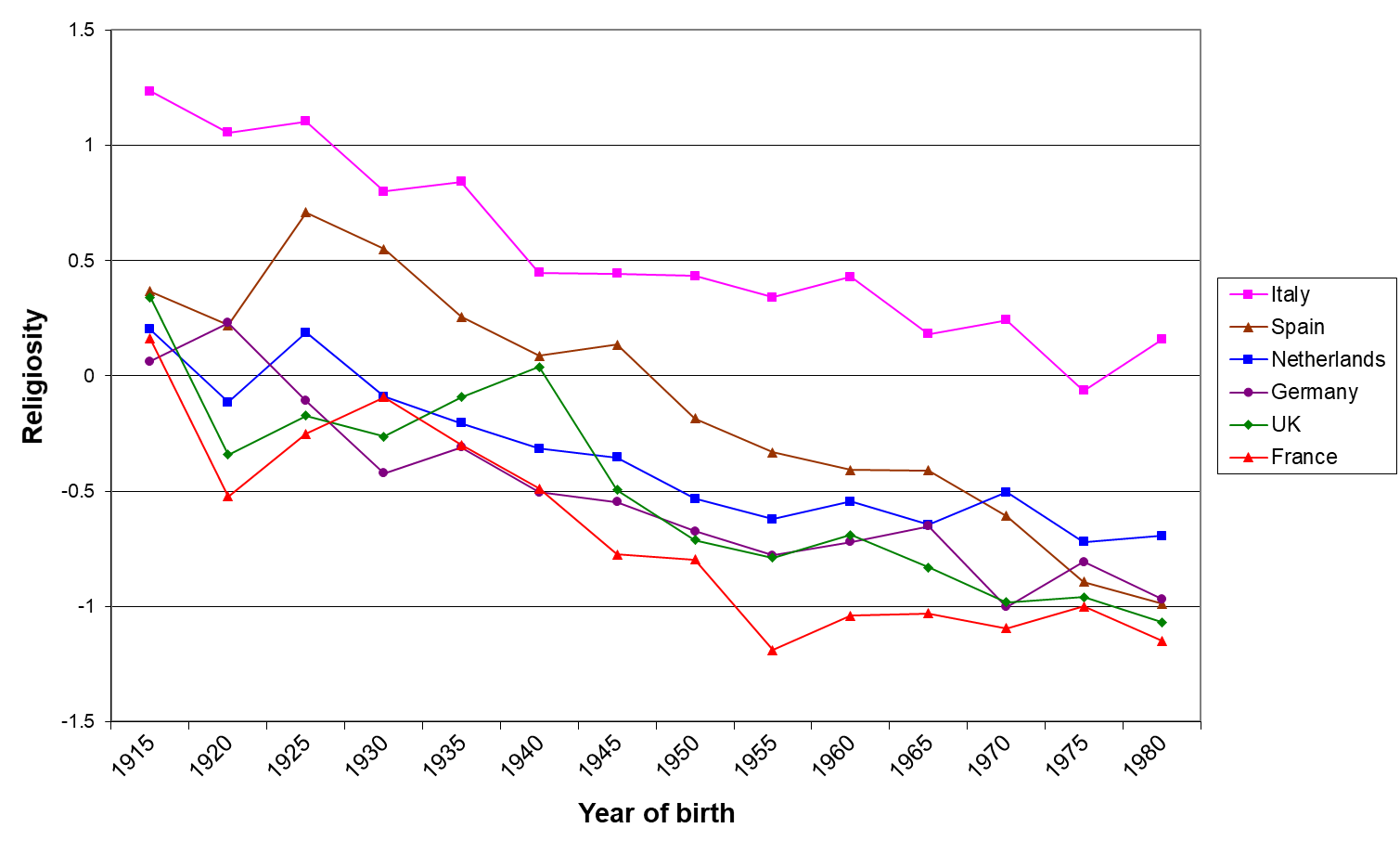

Contrary to claims that European countries so diverse that we cannot generalize about their religious trajectories (Greeley 2003), there is a remarkable uniformity in religious decline across the entire group included here. Fresh evidence comes from the European Social Survey, a new program covering all of these countries. A religiosity scale can be constructed using variables for religious affiliation, frequency of attendance and prayer, self-description as religious (or not), and importance of religion in life. While there are many variations– countries may be high or low in affiliation, attendance and belief– there is also an overriding theme: religion is in decline (see figure below). The magnitude of the fall in religiosity from the early to the late twentieth century has been remarkably constant across the continent, although the most religious countries are changing slightly more quickly than the least religious. The suggestion that the higher religiosity of earlier birth cohorts merely reflects an age-related return to faith can be rejected (Norris & Inglehart 2004, Voas 2004, Voas & Crockett 2005).

Despite suggestions that Europe is an exception, the timing and pattern of decline has in fact been very similar in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In 1946, a staggering 67 percent of Canadians claimed to have attended church in the previous week (Noll 2006). The figure has been falling steadily ever since and now stands at 19 percent (2003 General Social Survey), with 43 percent of people saying that they never attend. Among young adults the position is even more pronounced: half have no contact with religion at all and among those who do, most attend services only rarely. In New Zealand (in many respects a rather conservative country), 30 percent of the population now state that they have no religion (2001 census). Here too the trend is clear: a decade earlier the figure stood at only 20 percent. Among the elderly, Christian affiliation exceeds 85 percent and “no religion” is in single figures; among young adults, these two categories are level. The situation in Australia is similar; indeed, a number of commentators point to how closely it resembles the UK in both level and trends. Once again the direction of change is evident, whether one looks at a time series or at birth cohorts in cross-sectional data. The generational contrasts emerge clearly in the proportion of people identifying with no religion in the 1996 census: only 4 percent of those aged 70 and over, but 27 percent of those in their 20s, notwithstanding the immigration of young non-Christians.

The situation in Japan is harder to judge because of cultural differences, but the society seems highly secular. Although traditional ceremonies remain popular, the number of Japanese who claim to have no religious belief is increasing. “A 1994 poll indicated that less than seven percent of the population regularly took part in formal religious services” (US Department of State, 2000). According to a poll conducted by the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, only 20 percent of adults believe in any form of religion, a dramatic fall from the 1950 figure of 60 percent (Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance 2000). While the very low position of Japan in league tables of religious activity might be dismissed as irrelevant (because eastern religions, unlike Abrahamic faiths, do not emphasize regular collective worship), its similarly low ranking on the question of how important religion is in life is harder to ignore.

Of the 20 most modern nations in the world, then, 19 are becoming increasingly secular. These countries have very different histories, speak 11 different languages and are located on four different continents; we are not dealing here with a single culture. The apparent exception to the rule that modernization undermines religion is the United States.

The US has to some extent preserved traditional values while being highly modern in other respects; the nature of American exceptionalism will be developed further below. The twenty-first century, unlike the one before, will not be the American century, and it remains to be seen how long the US will remain an exception in the many ways that it is now. And although religion is undoubtedly strong in the United States, it is not popular with everyone. Political polarization may depress religious identification, leading more people to declare that they have no religion (Hout & Fischer 2002). Catholic attendance has fallen significantly in recent years, and the General Social Survey shows a decline in attendance generally between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s. Those who do attend Sunday services are less involved in other church activities than were earlier generations (Dixon 2004). The distinctiveness of the religious message is being diluted by individual and secular concerns; “In every aspect of the religious life, American faith has met American culture—and American culture has triumphed” (Wolfe 2003).

These various observations may or may not be harbingers of a secular transition. The key point at this stage is that the US is, at best, an exception. Of course most of the world is not secular, but then most of the world is not modern. The United States is the major world power, but to the scientific study of religion it is merely one society among many.

Religion undoubtedly remains strong in Latin America, Africa and the Islamic world. The countries that have the longest history of socio-economic development, however, tend to be the least religious. In South America, Uruguay is strikingly secular, and the beginnings of secularization may be detectable in Venezuela and Argentina. Nor is it merely a matter of European settlement and culture; the most developed countries in the Far East, including Singapore and Taiwan, seem quite secular, even if in a complicated way. A great question mark hangs over China, which has one-fifth of the world’s population and an economy that is already one of the largest in the world. When democracy and individual liberty arrive a religious revival will probably follow– but will it be sustained? In the long term, it seems more likely that most Chinese will continue to see religion as a private activity, to the extent that it is necessary at all.

Human nature and demand for religion

The basic axiom of the supply-side market model is that demand for religion is part of the human condition. The idea is a common one, and many different reasons have been advanced to support it, some rooted in evolutionary biology, others in psychology or sociology. Despite a certain plausibility, these arguments ultimately explain too much. It is hardly helpful to show why religion must be universally significant when it is obvious that religion is not now universally significant. Entire societies function without any significant public role for religion, and many millions of people have no religious beliefs and participate in no religious activities.

The degree of individual secularization is remarkable when one considers that disbelief in supernatural agency has only been rational for a period of about two lifetimes. Until Lyell and Darwin respectively showed how the inanimate and the animate had gradually evolved, it was difficult to avoid the conclusion that a divine watchmaker set the world in motion. Given how firmly rooted religious institutions were in society, and how few people change or abandon supernatural creeds inculcated in childhood, the extent of religious decline in Europe over the past 150 years seems little short of– dare one say it– miraculous. The relatively slow pace of change in most regions is hardly the problem that some contemporary sociologists would seek to make of it.

The example of fertility is instructive. By the 1960s demographic transition theory was in serious trouble. It was far from clear that there was, in fact, any close association between modernization and declining birth rates. No clear relationship had been found in the histories of the European regions between the main socio-economic indicators and the onset of reduced fertility. Nor were the patterns as might have been expected within regions; in late-nineteenth century England, for example, industrial workers tended to have higher fertility than others, and there was little difference between urban and rural areas. What was worse, many countries elsewhere in the world had reached levels of development and life expectancy that were superior to those obtaining in the West at the time of the transition, despite which they showed few signs of embarking on fertility control. Many commentators were convinced that, as the biologist Paul Ehrlich wrote, “the urge to reproduce has been fixed in us by billions of years of evolution ... The story in the UDCs [underdeveloped countries] is depressingly the same everywhere – people want large families” (Ehrlich 1968: 29, 83).

In short, demographic transition theory faced an equivalent of the Stark-Bainbridge thesis about the permanence of demand. Religion is supposed to promise something that no secular institution can offer, namely life after death. Likewise it was argued that children in traditional societies provided something that was not otherwise available, namely security in old age. Moreover the urge to reproduce is deeply embedded in human nature; not only do most of us have a powerful drive to mate, there is good evidence that most women, at least, have an urge to procreate. The grounds for thinking that birth rates would never come down in the absence of draconian social control were in fact far stronger than those for the corresponding view about religion. There was a definite fear in the 1960s and even later that voluntary birth control was a purely European phenomenon. The attempts to promote family planning in the developing world had enjoyed little success and in some cases were highly visible failures. What happened next was so unexpected, despite the long-standing notion of demographic transition, that it seemed as shocking as, say, widespread secularization. In one country after another, family sizes began to fall. In Japan, China, and East Asia generally, then in Latin America, India and finally even in the Muslim world and sub-Saharan Africa, the fertility transition finally took hold. By now there is no more talk of exceptions.

What we discovered is that human nature does not demand uncontrolled fertility. Moreover the evidence for the security motive (the economic afterlife provided by offspring) is remarkably weak. Reproductive behavior does not necessarily change once you give people pensions or other substitutes for family support, and conversely it has changed even in the absence of such alternatives. As powerful and as universal as the urge to reproduce apparently was, it is not inescapable. The alleged human need for religion seems unlikely to prove more durable.

Andrew Greeley has written a book entitled Unsecular Man: The Persistence of Religion. “Persistence” is the theme of much writing on the subject (The Persistence of Faith was the title used by the Chief Rabbi in Britain for a BBC lecture series in 1990), and indeed Robin Gill has used the term “persistence theories” to describe the view that religion will not lose its salience (Gill 1999). Similarly, a book edited by John Caldwell (perhaps the most distinguished demographer now living) that appeared no less recently than 1977 was entitled The Persistence of High Fertility. In the following years it became clear that high fertility would not, in fact, persist, and two decades later the festschrift that appeared on the occasion of Caldwell’s retirement was called The Continuing Demographic Transition. If secularization follows suit, the title of the present essay will be appropriate.

The impact of modernization

If demand for religion is not guaranteed, the next question is whether and how it is affected by modernization. Proponents of the secularization thesis point to the clear inverse relationship between socio-economic development and religious involvement; opponents cite the American exception and the persistent religiosity of societies that are now modernizing.

Modernization is a complex phenomenon, being even more difficult to define than religion and secularization. It may help to consider the impact of three separate features of modernization: material, institutional, and ideological. Material modernization is fairly straightforwardly economic and relates to the level, dispersion, and security of well-being. Institutional modernization refers to the extent to which the social and political systems are modern, that is, differentiation of the subsystems has occurred and participation is open to all. Ideological modernization is a matter of the degree to which authority has been displaced by individualism and a scientific and democratic worldview has taken hold.

The relationship between modernization and secularization is a fraught subject in part because each concept is multi-faceted. The argument in what follows is that the relevance of material modernization is often indirect, institutional modernization is highly important but can work in different ways, and ideological modernization may act as a proximal cause of change.

Material modernization

There is a tendency to assume that economic development must represent modernization, and it is indeed one part of it. But while material improvement is perhaps the most obvious form of modernization, it may actually be the least relevant to secularization in terms of direct effect. Becoming richer does not necessarily result in becoming less religious; it is a necessary but not a sufficient condition. The fact that an association exists between national prosperity and secularity at the global level probably reflects the extent to which development both encourages and to some extent depends on institutional or ideological modernization, with effects to be discussed in a moment.

The secular transition is a late product of modernization, not something that will start in the first stage of industrialization and urbanization. In a context in which faith is taken for granted, the proper form of religious practice becomes an issue. Society moves from a relaxed situation in which observance need not be frequent to one where identity demands participation. If you are going to claim to be Christian/Muslim/Hindu, you have to demonstrate some enthusiasm. Ultimately the effects of modernization are destructive, but its early stages can be associated with higher levels of religious participation.

In general, then, purely material modernization seems consistent with, and may even be encouraged by, active religiosity. While the absolute level of aggregate income is not necessarily decisive, though, the degree to which income is well distributed may be. The more evenly spread prosperity is, the less concentrated political influence and social control tend to be. It is difficult to sustain tradition when individuals have a sense of autonomy. Thus one finds an association between the strength of the state welfare system and the amount of religious practice in a country: the better the financial safety net, the less need for religious services (a generalization found in Wuthnow & Nass 1988 and elsewhere, and recently corroborated by Gill & Lundsgaarde 2004). What may be relevant is not the GDP per capita or some other measure of the level of prosperity, but rather the extent to which well-being is equitably distributed or at least reasonably secure for individuals. The thesis has been applied on a global scale with the claim that religious commitment is greatest where “existential security” is lowest (Norris & Inglehart 2004). To be contentious, one might suggest that financial and status anxiety, the lack of universal health care, fear of violent crime, and other features of individualized society in the United States have produced a culture of general insecurity.

Institutional modernization

The central feature of institutional modernization is well known: the functional differentiation of society into autonomous sub-systems. Government, the economy, religion, the family, and so on play their own separate roles and operate according to their own values, though of course there is a substantial measure of interdependence. Crucially, no single component holds sway over the others, neither God nor Mammon, not king, not patriarch. Modernization in its full sense also requires something more, namely the opportunity for everyone to participate in each sub-system, and to do so on at least roughly equal terms. Single-party states, command economies, lack of religious freedom, entrenched gender roles, etc. are features that make a country fall short of full modernity, however separate each sphere of action.

The freedom to participate (in the political process, in forming a family, in religion) carries with it the seeds of voluntary non-participation. Until this point is reached, however, the democratization that is part of institutional modernization may owe a debt to religious dissent, and it may repay that debt by encouraging religious pluralism rather than secularization. Thus religions can sometimes promote modernization in its early phases. It may be that Pentecostalism is having this sort of impact in Latin America; apart from anything else, conversion creates a break with the past, helping to undermine tradition.

The comparison with the fertility transition makes it less surprising that secularization has not proceeded in a linear fashion. It was not unusual to find birth rates rising in the early phases of modernization before subsequently declining: the initial impact of modernization is to put the resources of improved health, technological efficiency and mass communication at the service of traditional values. It is only when those values start to change that the transition sets in. To cite the rise of fundamentalism, liberation theology, Pentecostalism/charismatic renewal and so on as evidence against the thesis (Hadden 1995) is the equivalent of what might have been done in the early post-war period, when birth rates in many developing countries were higher than ever before. Indeed, it already seems that claims that religious movements in ex-Communist states represent a success for religious economies and a failure for the secularization thesis were premature. The story might well be the opposite. Religion has made remarkably little headway in eastern Germany, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and various other countries, despite extraordinarily large changes in religious market conditions in those places.

Ideological modernization

The final component of modernity is ideological, where the issue is how far a scientific and democratic worldview has taken hold. The connection with individual secularization seems clear, though of course there is a great danger of making the association trivial. If by definition a scientific worldview excludes the supernatural, then we have done no more than declare that individual secularization is an aspect of ideological modernity. There may be nothing wrong with doing so, but we could not then point to it as an empirical result.

In fact atheism is not a necessary feature of modern ideology. What is a feature, though, is a disposition to heterodoxy. No person or organization has privileged access to the truth. No statement– either religious or scientific– is truly authoritative. The worldview is scientific in part through its tendency to look for physical causes and solutions, but just as importantly in its promotion of the scientific method. Every claim is subject to criticism and testing. All pictures of reality are revisable.

Various scholars have highlighted this openness (to the new, the different, the individual, and the personal synthesis) in characterizing modernity. People are unwilling to judge one idea or style superior to another; tolerance is the only rule. Such a mindset may in the short term lead to religious creativity and a flowering of alternative spiritualities, but it is destructive of religious institutions.

Modernity brings about a shift in the relative value attached to the individual as opposed to the collective. Not only is the authority of the community diminished in control over behavior, it is also reduced in control over thought. Orthodoxy– right belief– becomes a foreign concept. No one has privileged access to power, and no one has privileged access to the truth. Everyone decides what is right him or herself, and everyone else is expected to be tolerant.

High religiosity, like high fertility, will persist the longest where individuals and households are tied most tightly into extended families and communities. Anyone familiar with Africa will know how difficult it is for even educated professionals to escape the bonds of traditional obligation. The notion of control– the changed relationship between the individual and his or her world– is an important link between the demographic and secular transitions. What seems to be crucial is not what people say they want, because that changes late and varies little across social strata, but rather their willingness to make non-traditional choices. It hardly needs to be said that a powerful, if complicated, result of modernization is precisely that kind of individual empowerment.

Grace Davie and others have reservations about the extent of individual secularization in part because they are not persuaded that ideological modernization has been very thorough. They refer to West Europeans being unchurched rather than secular, and assert that the decline in churchgoing has not resulted in a large number of conversions to secular rationalism. But surely the unchurching of Europe has been associated with just that, whatever words people use to describe themselves or their beliefs. They are far less inclined to see the supernatural around them than were our great-grandparents. Declared belief shows little real commitment to the idea of divine action in the world. The God of private belief is rather vague, and what people are prepared to do for God is even vaguer.

There remains the problem of the United States: is it modern in this final, ideological, sense? Parts of it undoubtedly are, but the dominant culture is remarkably traditional. In its ethnocentrism, nationalism and sense of mission, the US reminds us more of Victorian England than of contemporary Europe. The comparison need not be unilaterally unflattering; one might just as easily describe Europe as decadent as the US as backward. Late modern attitudes are founded in relativism, something to which mainstream American culture (as opposed to high culture) is considerably less prone than its European counterpart. Popular discourse is quite straightforwardly about good and evil, right and wrong, us and them. Such a climate is far more congenial to religion than the endlessly nuanced and situational morality of present-day Europe.

Clearly there is a danger in making ad hoc exceptions. What needs to be pointed out is simply that “the United States is not a prototype of cultural modernization for other societies to follow, as some modernization writers of the postwar era naively assumed. In fact, the United States is a deviant case, having a much more traditional value system than any other advanced industrial society” (Inglehart & Baker 2000: 31). Its old-fashioned ideology is manifested in politics, social policy and personal philosophies, not only in a propensity to be religious. To take a single example, American public authorities put to death one or more convicts every week; practically all other modern countries have decided that the execution of criminals is an unacceptable relic of earlier times. The direction of change is clear, though; just as it seems far more likely that the US will eventually abandon capital punishment than that European countries will readopt it, it is more probable that religion will decline in the US than be revived in Europe. Even today, it would be fascinating to see how Americans answered the question “Are you more or less religious than your parents were?” If “less” outnumbers “more,” the descent of the slippery slope is underway.

Mechanisms of change

Having established that societies can and do become predominantly non-religious and that modernization is relevant to such changes, the next question to consider is how secularization occurs (or is inhibited) in practice. In particular, the issue is whether low consumption of religion results from weak demand or problems of supply.

The importance of convention

Belief is subject to “social proof” and practice is governed by social norms, which means that there is considerable inertia to sustain either religion or its absence. Although in principle alternatives may be available, the exercise of choice is subject to social control. The availability of new options (e.g., contraception) or of new ways of thinking (e.g., about which gods rule or whether they do so at all) have little impact if there are strong social prohibitions.

In highly religious societies, appearing to be irreligious is not a viable option. When it comes to religion it is not the relatively secular European societies where choice is lacking, but rather the seriously religious ones, including the United States (see Kelley & de Graaf 1997). The fact that Tony Blair is more religious than 95 percent of his compatriots does not raise questions about his electability as prime minister; by contrast it is barely conceivable that a confessed atheist could be elected mayor of Dogpatch in the United States, much less president.

Of course social pressure remains significant, even if the secular transition has meant that its force is now felt in new ways. An Englishwoman interviewed in 1945 remarked that it had become the custom to have just two children, saying “A family of five or six children loses in prestige and, some think, in respectability” (Levine 1985: 202). This is surely the position with regards to churchgoing in England today: it has lost prestige and even, for some, respectability.

The most religious societies in the world are those monopolized by a single faith (usually Islam). The most religious countries in Europe– Greece, Italy, Poland, and Ireland– are dominated by a single church. Even the supposed exceptions do not seem so exceptional. In Sweden, belief in the supernatural is low but baptism, confirmation and membership are very high by European standards– a reflection of the Church of Sweden’s role in national life.

The United States is supposed to be the great example of how diversity promotes participation, and it should be granted immediately that it is an impressive case. Nevertheless the observer might also note how cultures have become homogenized and differences lost. Religion was not exempt from the melting pot. One hundred or so years ago the variety of belief and practice was greater than it is today. A number of Protestant religious groups thought it sinful to dance or play cards. The full and distinctive richness of peasant Catholicism and shtetl Judaism were available. Since then, theology and behavior have regressed towards the mean. Mormons are monogamous, Methodists drink, Jews believe in an afterlife and Catholics are little different from Protestants. Denominations struggle to maintain an identity. President Dwight D. Eisenhower said more than he realized when he declared that “In our fundamental faith, we are all one.”

The great achievement of the United States is imprinted on its seal: E pluribus unum. The emphasis is on the one rather than the many, and it applies to religion as well as nationality. There is a taken-for-grantedness about God in America that amounts to a sacred canopy; the beliefs that are shared are more important than the details that are not. There is constant reinforcement of generic religion in everyday encounters; what is so striking to visitors from Europe is how many Americans really do talk about God without apparent constraint and assume that others will belong to a church.

The irony is that supporters of supply-side theory hold up the US as an example of a religious free market when both official policy and popular culture do more to promote generic religion than anywhere else in the modern world. Every day children all over the United States stand, face the flag, place their hands over their hearts, and swear loyalty to “one nation, under God.” As President Eisenhower declared, those “millions of our school children will daily proclaim … the dedication of our Nation and our people to the Almighty.” The essential feature of this activity is that religion is associated with love of country, not merely promoted (e.g., through prayer) for its own sake. Every child will be exposed to this state-sponsored conditioning thousands of times before reaching the age of mature choice, which is hardly consistent with the view that there is no official interference in the American religious market.

The other irony is that supply-side explanations do not fit the facts even in the United States. The idea that the average degree of religious commitment depends largely on the amount of competition in the religious “marketplace” is clearly false in global perspective: the most religious countries have the most monopolistic suppliers (Islam in Asia, Catholicism in Europe). It is just as false in the US, where the most religious states and counties are those most dominated by a single denomination, be it Baptist, Catholic or Mormon. Those counties where three-quarters or more of adherents belong to one denomination have on average 63.5 percent of the population in some religious group; by contrast only 47.6 percent are adherents in counties where no denomination accounts for more than a third (ASARB / Glenmary, 2000 statistics).

In short, there is little evidence that a large choice with no dominant supplier helps religion. This situation is not hard to understand even in terms of a market model. For example, consumers do not want lots of choice in computer operating systems; they want something stable, secure and widely used that offers a good platform for other activities. (The parallel with religion should be obvious.) Most are happy with Microsoft Windows, and those that are not can go to Apple or Linux. Having dozens of competing operating systems would hurt, not help, the market.

Demand may collapse for reasons that are unrelated to the structure of the market, and changes that boost consumption in the short term may undermine it in the long term. Religion requires a consensus that it is needed, and it is often easiest to maintain such a consensus if one variety is universal. Neckties are worn most when everyone is expected to wear a tie. Variety may for a time increase the size of the market: people try different styles and colors. The more variety is allowed, though, the more fragile the custom becomes; sooner or later someone in the vanguard will try the cartoon tie, the string tie, and the untied tie. For anything non-essential, with real costs and intangible benefits, the end point of choice is to dispense with the product. There may a wonderful variety of necktie suppliers competing vigorously in a free market, all to no avail: people may stop teaching their children that they are undressed without a tie. Demand for religion is the same: it is sustained not by the vigor of the market but by deeply rooted social expectations.

The US is unusual in maintaining a strong religious tie-wearing norm even while permitting wide latitude in choice. The remarkable thing about religion in America is that people have decided that faith is quasi-mandatory even though no single faith is (officially) preferred over others. As Eisenhower famously put it, “Our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” The vibrant and diverse religious culture in the US may be a source of religious strength, but it relies on a general acceptance of religion itself (which as we have seen is vulnerable to erosion).

Behavioral drift

The rational choice approach to family size was based on showing why people did or did not see fertility reduction as advantageous. The seemingly innocuous assumption that reduction must first be recognized as beneficial is mistaken, however. The fertility transition often starts before any reduction in what people claim are their preferred family sizes. Far from being the conscious result of reduced demand, fertility declines and then attitudes have to catch up. Likewise religious decline does not result from prior deliberate choices about the value of religious practice; instead, a kind of decay in patterns of observance only subsequently feeds into conscious perceptions of what is or is not beneficial.

The same phenomenon is important in the study of social capital. Robert Putman (2000) suggests that the time devoted to watching television bears much of the blame for the decline in participation in voluntary associations. That can be true, though, even if no one says “I’ve decided to give up going to my church club so that I can spend more time at home watching TV.” There is no cold calculation of long-term benefit; rather, it all starts as a matter of short-term expedience. The term “behavioral drift” has been aptly used to describe the process.

There is a large difference between voluntary association and involuntary community: a person belonging to something like a badminton club may feel some personal commitment to the activity but not a strong sense of social obligation (Bruce 1999: 169-70). We can imagine how this commitment might disintegrate. The first stage comes on the cold evening that, sitting by the fire, the person decides he would really rather stay in– and who could blame him? If asked, though, he would still say that he is an active member of the club. The second stage is when he has developed something of a taste for staying home by the fire, and is now skipping more than he is attending. He would still describe himself as a badminton player, though, even if not necessarily an active member and perhaps his conscience is sufficiently uneasy about it that he exaggerates his participation. Ultimately the day will come when not only has he not played for months or even years, he realizes that in fact he cannot play any longer– or even if he still can, his children, who used to go with him, have no interest or residual ability. In this final stage, there are two possible attitudes and forms of rationalization. He can continue to claim in the face of the evidence that he is still a player, arguing the equivalent of the familiar notion that “you don’t have to go to church to be a good Christian.” Alternatively he can admit that he is no longer involved in the sport, in which case he may say that badminton was never really worthwhile.

Even though it has taken him years to reach the point of admitting it, we might want to argue that a failure of belief was long ago implicit in his practice. While that is a possible approach, it seems more useful to recognize that the roads to hell, couch-potato-hood and many other destinations are paved with good intentions. Many women who came of age in recent decades expressed their rational choice to have children and went on expressing it year after year until they reached their forties, all the while making micro-choices that diverted them from that goal. Do we accuse them of bad faith, false consciousness, and irrationality? No, we understand that many situations are the unintended consequences of sensible decisions taken by people who might in fact have wished for something entirely different. The methodological problem that faces social scientists is that neither self-reported motivation nor a simple interpretation of behavior may get at the truth, which may not be complicated but is often messy.

Diffusion

The perceived failure of both macro- and micro-economic accounts of fertility change helped to direct attention towards more sociological explanations, particularly those dealing with concepts of culture and diffusion. There is a considerable body of evidence to support the importance of culture, as opposed to socio-economic factors, for fertility. The transition tends to occur in culturally related regions all at once, however different those regions are in terms of industry, standard of living, or degree of urbanization. Conversely it may occur at different times in places that are culturally distinct, however close they might be geographically (Lesthaeghe 1977).

One benefit of diffusion models is that early and late adopters can act in the same way for different reasons. Apostles might be persuaded by doctrine, for example, while subsequent converts may be motivated by non-cognitive factors. (A celebrity may choose a hairstyle to match her features, while others choose to match her choice). It is necessary to explain how and why the innovation came to be adopted, but the story need not be the same for everyone (though it should be coherent and generalizable). Thus the fact that so few non-churchgoers are avowed atheists does not mean that atheism was unimportant as a force, if early unbelievers acted as trendsetters. Consideration of diffusion forces us to pay attention to the social networks involved.

One of the apparent paradoxes of European fertility decline is that it began before so-called appliance methods of birth control became widely available or affordable. On the other hand, books on family planning were in circulation. It is possible to argue that these debates, like the similar Victorian debates over discoveries in biology and geology, were important more for their existence than their content. For ordinary people there was probably little likelihood of following the recommendations in The Wife’s Handbook, any more than of becoming convinced Darwinians. Nonetheless the mere existence of the discussion might have been significant in bringing such matters into the “calculus of conscious choice,” even if the points themselves were not adopted (Woods 1987). Battles in the public arena over what is published, whether it is Lady Chatterley’s Lover or works of Holocaust denial, are so fraught precisely because we understand the legitimizing effect of dissemination. The popular picture of science exploding the foundations of faith is far from being an accurate representation of what occurred; nevertheless the thinkability of unbelief radically changed in the 19th century, as did the thinkability of contraception within marriage. It remains an open question, however, whether the introduction of ideas or the demonstration of behavior has the greater effect.

The irreversibility of secularization

The argument thus far has been that demand for religion may go down, that modernization tends to undermine it, and that the mechanisms by which secularization occurs are not difficult to understand. The final step is to show that substantial declines in demand for religion are usually permanent; religion is no more likely to be revived in modern secular societies than is child labor. By contrast, Stark and others maintain that religious downturns are merely part of a cycle governed largely by what is on offer (Stark & Bainbridge 1985). There are two key objections to this supply-side story: secularization comes as part of the package of advanced modernity, and modernization is irreversible.

The inseparability of the various transitions could be regarded as the main element of modernization theory. There is little point in talking about modernization at all unless we believe that modernity is characterized by a number of essential features; the question is simply what they are. The hypothesis that fertility decline is part of the package, and that it would come to all parts of the world as modernization spread, was advanced more than 50 years ago. During much of that period the proposition seemed dubious, but it has now been vindicated. The theory of the secular transition– or the secularization thesis, as it is commonly called– is similarly under challenge today.

Theories of modernization were rightly attacked in recent decades for their quasi-Marxist flavor, whereby all changes were seen as being driven by economic transformations. If we include cultural or ideological characteristics in the package of modernity, however, and do not view them as necessarily secondary to material factors, then notions of modernization seem much less suspect.

Development is driven by rational choice, which is to say by people seeking to satisfy their preferences with the means available. These preferences are shared by most human beings. We all want to be healthy, to live longer, to live in greater comfort, and to have more resources at our disposal. Occasionally people choose differently, but they are very rare, even in societies that revere ascetics. Likewise we all tend to want a measure of control or at least influence in our societies, to feel that we are at no one else’s mercy and are not inferior to any other person. We do not want our personal interests subordinated to the group’s without very good reason. To a very considerable extent these more or less universal human desires determine the course of development in such a way that there are not, in fact, multiple modernities. What is true is that the preferences underlying some aspects of ideology in particular may push in multiple directions, so that change is slow and erratic.

The concept of globalization is in a sense the successor to modernization; the idea is that the structure of the modern world is making places more alike in certain ways. If modernization is unstoppable, then secularization will spread as did fertility control, free markets and liberal democracy. It is a constituent element of the same process, cause and effect of all the other components. Different aspects of modernity may arrive in a different order, or after different lag times, depending on local conditions; that does not change the fact that they all do, eventually, arrive.

The various features that will go up, or down, include the following:

DOWN

poverty

insecurity

illiteracy

mortality

fertility

extended families

community

nationalism

religion

Predictions in social science are viewed with suspicion, especially when they seem to imply a kind of inevitability that was labeled “historicism” by Popper (1957). Certainly events may surprise us, and no social predictions enjoy the sort of confidence we attach to physical regularities. That said, it seems clear that some social phenomena are cyclical or haphazard (e.g., conflict) and others are genuinely directional: it is hard to imagine going backwards. Does anyone think that slavery is going to be revived, or that polygamy will become more rather than less common throughout the world? Erosion of both fertility and religion appear to belong in the “directional” rather than the “cyclical” category, though there will obviously be many revivals of a local and temporary nature.

Some scholars object that the idea of development seems to imply a goal, and hence progress towards that goal, and thus a normative view that some societies are better than others. (One feature of modern ideology, of course, is a reluctance to judge anything better than anything else– which can make it hard to say even that tolerance is superior to intolerance.) What we are considering is a kind of evolution, though, and as Darwin taught us evolution does not need to be teleological. There is no goal, no end point, and the traits that survive are superior only in being better adapted to the environment.

Of course it would be dishonest to pretend that we do not regard the modern as better than the traditional. In a strict sense, however, this normative judgment is independent of the question of whether societies really do tend to develop in certain common directions. It would be entirely consistent– and not even very unusual– to assert that the world is changing in a particular way and to decry that development.

The suggestion is simply that modernity has a kind of momentum that is difficult to resist, and that in consequence all kinds of social changes (including improvements in the status of women, the spread of liberal democracy, etc., not just secularization) will tend to occur in more and more places. That does not mean that there will not be people and societies swimming against the tide, and naturally it is always possible that some kind of catastrophe or unanticipated development might turn things around. Nothing is inevitable, but some outcomes seem more probable than others.

In recent research, Iannaccone (2003) uses retrospective data from 34 countries to construct trends in child and adult church attendance over the course of the 20th century. No country in his sample displays steadily increasing attendance, nor does any low-attendance country ever shift to a higher long-run level. In no country was religious activity higher at the end of the period than at the beginning, and in most it is significantly lower. The countries concerned are mainly Western, but they include cases such as the United States, Poland, the Philippines and Israel that are generally regarded as having had stable levels of adherence. The movement even in these places (e.g., among Catholics and children in the US) is negative to the extent that there is any sign of a trend. Nowhere has demand dropped and later rebounded for any sustained period. Secularization is a one-way street.

The geography of transition

Just as the fertility transition swept through most of Western Europe and the European New World within a fairly short period, so there has also been a high degree of synchronization within other cultural zones: East Asia, Latin America, India, and perhaps the Islamic world and finally sub-Saharan Africa. Viewed from the mid-20th century, there would certainly have appeared to be a Western exceptionalism about low fertility: not only was there little sign of it elsewhere, there seemed to be little prospect of it. And yet it happened. The secular transition will not operate as quickly, but it will happen eventually. Economic development is gradual and institutional and ideological modernizations are slow to take root. Even when these things have been achieved there will be episodes of reaction, and pockets of tradition will hold out for generations. Ultimately, however, the world will be modern and secular. Religion will survive, as astrology has survived, but its significance will be much reduced.

The fertility transition has occurred with striking simultaneity, not just within individual societies or nations, but across whole continents or cultures. If we divide the globe into cultural zones, the order by onset of fertility decline would be something like the following:

France

Northern/Western Europe & overseas dominions

Southern/Eastern Europe & Russia

Japan / China / East Asia

Latin America

India

North Africa, Middle & Near East

Sub-Saharan Africa

One could conjecture that secularization will spread across the world in essentially the same order, although the US may drop a place or two. There is no space for a detailed defense of this claim, but a few comments are appropriate. If we divide these large zones into smaller, sub-national regions we find (as mentioned earlier) that the secular and fertility transitions occurred in the same order, which offers some support to the hypothesis that the same will be true on a global scale. The regional pattern of secularization in Europe corresponds closely to the date of onset of fertility decline. It is therefore not a little intriguing that Uruguay, the country in South America that entered the fertility transition in the late 19th century, many decades before the rest of the continent, is now remarkably secular. Argentina, which followed it in fertility decline, is likewise on the road to secularization.

Western Europe, the old British Commonwealth and arguably Eastern Europe are well along on the secular road, and East Asia is heading the same way. Latin America remains relatively religious, but a case can be made that the dramatic surge of Protestantism is the first step toward secularization, just as the Reformation proved to be the first step in Europe. Religious decline in the last three zones is obviously a long way off, but not as inconceivable as is often thought.

Dudley Kirk, one of the early proponents of the demographic transition, has written that “Its greatest strength is the prediction that the transition will occur in every society which is experiencing modernization; its greatest weakness its inability to forecast the precise threshold required for fertility to fall.” Explaining the timing of onset of religious decline remains the great question, just as it was and is with fertility.

Conclusion

The other great transitions of modernity– in particular the demographic transition– might have something to teach us about secularization, specifically:

• Human desires that seem universal and immutable may turn out not to be so.

• For there to be rational action, there must be options.

• Social control can be more important than individual choice.

• Effective action can occur in the absence of preferences for its ultimate consequence.

• Preferences and values can spread independently of the beliefs that gave rise to them.

• The influence of public policy is limited, but official action can sometimes be effective in hastening or delaying the onset of transition.

• Transitions occasionally may be prolonged or interrupted, but generally they do not stop once started.

• There is spatial-temporal sequence in transitions.

While we should look carefully at differences between places, what is striking about transitions is the way they are reproduced across national and economic divides. We must also be open to the possibility of surprise. Anyone writing on this subject in the 1960s would have highlighted the failure of family planning programs across the less developed world and the apparent intractability of pronatalist attitudes. The message for secularization theorists would almost certainly have reinforced ideas of European exceptionalism. By now, though, it is apparent that Europe is the bellwether, not the exception. Of course there were large campaigns to reduce birth rates, and there will be no such official action against religiosity: rather the reverse. For these and other reasons secularization should not be expected to proceed as rapidly as declining fertility.

About the fact of secularization– at the individual as well as the social level– there can hardly be much doubt. The most comprehensive international evidence comes from the World Values Survey (WVS), and from this source “the central prediction of modernization theory finds broad support: Economic development is associated with major changes in prevailing values and beliefs: The worldviews of rich societies differ markedly from those of poor societies” (Inglehart & Baker 2000: 49-50). Two economic variables alone (GDP per capita and the percentage employed in the industrial sector) account for 42 percent of the variance in the levels of traditional vs. secular-rational values across 65 nations; the addition of dummy variables for three cultural regions raises the adjusted R2 to 70 percent (Inglehart & Baker 2000: 39). Regressions featuring indices of state regulation or other measures favored by supply-side theorists come nowhere close to these levels of explanatory power. Economists have not so far even been able to identify a consistently positive or negative effect of church establishment, however small (see Iannaccone 1991 on the one hand and McCleary & Barro 2006 on the other).

The great problem for theorists of the secular transition– just as for demographers dealing with the fertility transition– is to specify the mechanisms that are likely to produce change and to assess the significance of initial conditions. The process will not necessarily be the same everywhere; “The persistence of distinctive value systems suggests that culture is path-dependent” (Inglehart & Baker 2000: 37). The details seem elusive and the state of theory is frankly unsatisfactory; clearly modernization theorists have work to do. To predict that certain transitions will occur without a satisfactory explanation of when or exactly why would be an odd kind of social science. Still, there is a big picture: societies around the world have undergone a number of major identifiable changes, and these changes are systematically related to what happens during modernization. The relationship is complex, but it is not coincidental. Ongoing research will help to clarify the mechanisms by which secularization might be triggered, delayed or even avoided. The religious economies model could have a role here, and at least some scholars might be open to a degree in syncretism in combining elements of supply- and demand-side explanations.

Thus far, though, the religious economies model looks like a theory constructed on the experiences of a single country, and the attempts to apply it outside the Western hemisphere do not really hold up under close examination. In any event, it is far from clear that the secularization paradigm was wrong about the United States. (Whether or not it has been useful is a different question.) The US has managed to retain the key feature of the sacred canopy: faith is taken for granted (even if its details are not). Self-description as a “religious person” is just as high in the US as in Iran, according to the WVS (Moaddel & Azadarmaki 2003: 75). The challenge is to explain how the religious worldview was maintained and even strengthened since the establishment of the republic, while in Europe such sacred canopies have gradually folded. An acceptance of pluralism may be relevant. Whether disestablishment per se really matters is more doubtful: after all, there was an extremely– sometimes excessively– vibrant religious economy in 17th, 18th and especially 19th-century Britain. Levels of weekly church attendance in mid-19th century England and Wales approached 60 percent (Crockett 1998), possibly higher than has ever been achieved at a national level in the US. The parallels between Victorian Britain and post-war America a century later go very deep: these are nations convinced of their moral superiority, military invincibility and divine protection. When imperial over-reach leads to a shift in the global balance of economic and political power, the stage may be set for secularization.

The Victorians had just as much confidence in the strength of their religious economy as Americans do today. The hazards of crystal-ball gazing can be seen in material form in Liverpool, where a century ago civic and religious leaders felt the need to have not one but two major cathedrals. The Anglican cathedral– the largest in the country– was finally finished in 1978, by which time its constituency was starting to collapse. The Catholic cathedral would have been truly monumental had it followed the original plan, rivaling St. Peter’s in Rome. That design was only abandoned after the interruption caused by the Second World War, and the building eventually completed was highly modern and on a much reduced scale. A few decades on, the Catholic Archbishop is closing churches and has serious problems finding priests for his dwindling flock.

We may draw two morals from such stories. The first is that while religion has continued to attract adherents for longer than some social philosophers might have expected, it has not done so well as its promoters anticipated– and may not do so well indefinitely in places where it is now strong. The second is that predicting social change is uncomfortably close to prophecy, and prophecy, in our own era, does not have a distinguished record. We shall all be in our graves before the truth about secularization is known.

References

Bruce, Steve. 1999. Choice and Religion: A Critique of Rational Choice Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bruce, Steve. 2002. God is Dead: Secularization in the West. Oxford: Blackwell.

Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Crockett, Alasdair. 1998. A Secularising Geography? Patterns and Processes of Religious Change in England and Wales, 1676-1851. Ph.D. thesis; University of Leicester.

Davie, Grace. 2000. Religion in Modern Europe: A Memory Mutates. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davie, Grace. 2002. Europe: the Exceptional Case. Parameters of Faith in the Modern World. London: Darton, Longman & Todd.

Dixon, Bob. 2004. “Parish Involvement Scores of Generation X Mass Attenders in the United States and Australia.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Kansas City, October 23, 2004.

Ehrlich, Paul. 1968. The Population Bomb. New York: Sierra Club-Ballantine.

Gill, Anthony, and Erik Lundsgaarde. 2004. “State Welfare Spending and Religiosity: A Cross-National Analysis.” Rationality and Society 16(4): 399-436.

Gill, Robin. 1999. Churchgoing and Christian Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Greeley, Andrew. 2003. Religion in Europe at the End of the Second Millennium. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Hadden, Jeffrey K. 1995. “Religion and the Quest for Meaning and Order: Old Paradigms, New Realities.” Sociological Focus 28(1): 83-100.

Hout, Michael, and Claude Fischer. 2002. “Why More Americans Have No Religious Preference: Politics and Generations.” American Sociological Review 67(2): 165-190

Iannaccone, Laurence. 1991. “The Consequences of Religious Market Structure: Adam Smith and the Economics of Religion.” Rationality and Society 3(2): 156-77.

Iannaccone, Laurence. 2003. “Looking Backward: A Cross-national Study of Religious Trends.” Working paper. http://gunston.gmu.edu/liannacc/ERel/S2-Archives/S21_Publications.htm

Inglehart, Ronald, and Wayne E. Baker. 2000. “Modernization, Cultural Change, and the Persistence of Traditional Values.” American Sociological Review 65(1): 19-51.

Kelley, Jonathan, and Nan Dirk de Graaf. 1997. “National Context, Parental Socialization, and Religious Belief: Results from 15 Nations.” American Sociological Review 62(4): 639-659.

Lesthaeghe, Ron. (1977) The Decline of Belgian Fertility, 1800-1970. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Levine, David. 1985. “Industrialization and the Proletarian Family in England.” Past and Present 107: 168-203.

McCleary, Rachel M., and Robert J. Barro. 2006. “Religion and Political Economy in an International Panel.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45(2): 149-175.

Moaddel, Mansoor, and Taqhi Azadarmaki. 2003. “The Worldview of Islamic Publics: The Cases of Egypt, Iran, and Jordan,” in Human Values and Social Change: Findings from the Values Surveys, ed. Ronald Inglehart, 69-89. Boston, MA: Brill.

Noll, Mark A. 2006. “What Happened to Christian Canada?” Church History 75(2): 245-73.

Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2004. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. 2000. “Worldwide News of Religious Intolerance & Conflict for 2000-jun” http://www.religioustolerance.org/news_00jun.htm

Popper, Karl. 1957. The Poverty of Historicism. Boston: The Beacon Press.

Putman, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Stark, Rodney, and William Sims Bainbridge. 1985. The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival and Cult Formation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. 2000. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

US Department of State. 2000. 2000 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom: Japan. http://www.state.gov/www/global/human_rights/irf/irf_rpt/irf_japan.html

Voas, David. 2004. “Religion in Europe: One Theme, Many Variations?” Paper presented at the conference on Religion, Economics and Culture, Kansas City, October 2004.

Voas, David, and Alasdair Crockett. 2005. “Religion in Britain: Neither Believing nor Belonging.” Sociology 39(1): 11-28.

Wolfe, Alan. 2003. The Transformation of American Religion: How We Actually Live Our Faith. New York: Free Press.

Woods, Robert. 1987. “Approaches to the Fertility Transition in Victorian England.” Population Studies 41(2): 283-311.

Wuthnow, Robert, and Clifford Nass. 1988. “Government Activity and Civil Privatism: Evidence from Voluntary Church Membership.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 27(2): 157-174.

To cite this paper:

Voas, David (2007) The continuing secular transition, in The Role of Religion in Modern Societies, ed. D Pollack and DVA Olson. Routledge, pp. 25-48.

An earlier version was presented at the annual conference of the BSA Sociology of Religion Study Group, which took place at the University of Exeter (UK) on 29 March-1 April 2000. The conference honoured the contributions of David Martin and Bryan Wilson; its theme was “Prophets and Predictions”.

UP

technology

industrialization

urbanization

bureaucratization

communications

gender equality

liberal democracy

free markets

individualism